First Australian Imperial Force on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The First Australian Imperial Force (1st AIF) was the main expeditionary force of the

When originally formed in 1914 the AIF was commanded by Bridges, who also commanded the 1st Division. After Bridges' death at Gallipoli in May 1915, the Australian government appointed

When originally formed in 1914 the AIF was commanded by Bridges, who also commanded the 1st Division. After Bridges' death at Gallipoli in May 1915, the Australian government appointed

The 1st AIF included the

The 1st AIF included the

The weaponry and equipment of the Australian Army had mostly been standardised on that used by the British Army prior to the outbreak of World War I. During the war the equipment used changed as tactics evolved, and generally followed British developments. The standard issued rifle was the .303-inch Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mark III (SMLE). Infantrymen used 1908-pattern webbing, while light horsemen used leather

The weaponry and equipment of the Australian Army had mostly been standardised on that used by the British Army prior to the outbreak of World War I. During the war the equipment used changed as tactics evolved, and generally followed British developments. The standard issued rifle was the .303-inch Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mark III (SMLE). Infantrymen used 1908-pattern webbing, while light horsemen used leather

The recruitment process was managed by the various military districts. At the outset it had been planned to recruit half the AIF's initial commitment of 20,000 personnel from Australia's part-time forces, and volunteers were initially recruited from within designated regimental areas, thus creating a linkage between the units of the AIF and the units of the home service Militia. In the early stages of mobilisation the men of the AIF were selected under some of the toughest criterion of any army in World War I and it is believed that roughly 30 percent of men that applied were rejected on medical grounds. To enlist, men had to be aged between 18 and 35 years of age (although it is believed that men as old as 70 and as young as 14 managed to enlist), and they had to be at least , with a chest measurement of at least . Many of these strict requirements were lifted later in the war, however, as the need for replacements grew. Indeed, casualties among the initial volunteers were so high, that of the 32,000 original soldiers of the AIF only 7,000 would survive to the end of the war.

By the end of 1914 around 53,000 volunteers had been accepted, allowing a second contingent to depart in December. Meanwhile, reinforcements were sent at a rate of 3,200 men per month. The landing at Anzac Cove subsequently resulted in a significant increase in enlistments, with 36,575 men being recruited in July 1915. Although this level was never again reached, enlistments remained high in late 1915 and early 1916. From then a gradual decline occurred, and whereas news from Gallipoli had increased recruitment, the fighting at Fromelles and Pozieres did not have a similar effect, with monthly totals dropping from 10,656 in May 1916 to around 6,000 between June and August. Significant losses in mid-1916, coupled with the failure of the volunteer system to provide sufficient replacements, resulted in the first referendum on conscription, which was defeated by a narrow margin. Although there was an increase in enlistments in September (9,325) and October (11,520), in December they fell to the lowest total of the year (2,617). Enlistments in 1917 never exceeded 4,989 (in March). Heavy losses at Passchendaele resulted in a second referendum on conscription, which was defeated by an even greater margin. Recruitment continued to decline, reaching a low in December (2,247). Monthly intakes fell further in early 1918, but peaked in May (4,888) and remained relatively steady albeit reduced from previous periods, before slightly increasing in October (3,619) prior to the

The recruitment process was managed by the various military districts. At the outset it had been planned to recruit half the AIF's initial commitment of 20,000 personnel from Australia's part-time forces, and volunteers were initially recruited from within designated regimental areas, thus creating a linkage between the units of the AIF and the units of the home service Militia. In the early stages of mobilisation the men of the AIF were selected under some of the toughest criterion of any army in World War I and it is believed that roughly 30 percent of men that applied were rejected on medical grounds. To enlist, men had to be aged between 18 and 35 years of age (although it is believed that men as old as 70 and as young as 14 managed to enlist), and they had to be at least , with a chest measurement of at least . Many of these strict requirements were lifted later in the war, however, as the need for replacements grew. Indeed, casualties among the initial volunteers were so high, that of the 32,000 original soldiers of the AIF only 7,000 would survive to the end of the war.

By the end of 1914 around 53,000 volunteers had been accepted, allowing a second contingent to depart in December. Meanwhile, reinforcements were sent at a rate of 3,200 men per month. The landing at Anzac Cove subsequently resulted in a significant increase in enlistments, with 36,575 men being recruited in July 1915. Although this level was never again reached, enlistments remained high in late 1915 and early 1916. From then a gradual decline occurred, and whereas news from Gallipoli had increased recruitment, the fighting at Fromelles and Pozieres did not have a similar effect, with monthly totals dropping from 10,656 in May 1916 to around 6,000 between June and August. Significant losses in mid-1916, coupled with the failure of the volunteer system to provide sufficient replacements, resulted in the first referendum on conscription, which was defeated by a narrow margin. Although there was an increase in enlistments in September (9,325) and October (11,520), in December they fell to the lowest total of the year (2,617). Enlistments in 1917 never exceeded 4,989 (in March). Heavy losses at Passchendaele resulted in a second referendum on conscription, which was defeated by an even greater margin. Recruitment continued to decline, reaching a low in December (2,247). Monthly intakes fell further in early 1918, but peaked in May (4,888) and remained relatively steady albeit reduced from previous periods, before slightly increasing in October (3,619) prior to the

In the early stages of the AIF's formation, prior to Gallipoli, training was rudimentary and performed mainly at unit-level. There were no formal schools and volunteers proceeded straight from recruiting stations to their assigned units, which were still in the process of being established. Upon arrival, in makeshift camps the recruits received basic training in drill and musketry from officers and non-commissioned officers, who were not trained instructors and had been appointed mainly because they had previous service in the part-time forces. Camps were established in every state including at Enoggera (Queensland),

In the early stages of the AIF's formation, prior to Gallipoli, training was rudimentary and performed mainly at unit-level. There were no formal schools and volunteers proceeded straight from recruiting stations to their assigned units, which were still in the process of being established. Upon arrival, in makeshift camps the recruits received basic training in drill and musketry from officers and non-commissioned officers, who were not trained instructors and had been appointed mainly because they had previous service in the part-time forces. Camps were established in every state including at Enoggera (Queensland),  After the AIF was transferred to the European battlefield, the training system was greatly improved. Efforts were made at standardisation, with a formal training organisation and curriculum—consisting of 14 weeks basic training for infantrymen—being established. In Egypt, as the AIF was expanded in early 1916, each brigade established a training battalion. These formations were later sent to the United Kingdom and were absorbed into a large system of depots that was established on Salisbury Plain by each branch of the AIF including infantry, engineers, artillery, signals, medical and logistics. After completing their initial instruction at depots in Australia and the United Kingdom, soldiers were posted to in-theatre base depots where they received advanced training before being posted as reinforcements to operational units. Like the British Army, the AIF sought to rapidly pass on "lessons learned" as the war progressed, and these were widely transmitted through regularly updated training documents. The experience gained through combat also improved the skills of the surviving officers and men, and by 1918 the AIF was a very well trained and well led force. After coming to terms with the conditions on the Western Front the Australians had played a part in the development of new combined arms tactics for offensive operations that occurred within the BEF, while in defence they employed patrolling, trench raids, and Peaceful Penetration tactics to dominate no man's land.

Following the deployment of the AIF a reinforcement system was used to replace wastage. Reinforcements received training in Australia first at camps around the country before sailing as drafts—consisting of about two officers and between 100 and 150 other ranks—and joining their assigned units at the front. Initially, these drafts were assigned to specific units prior to departure and were recruited from the same area as the unit they were assigned to, but later in the war drafts were sent as "general reinforcements", which could be assigned to any unit as required. These drafts were despatched even before Gallipoli and continued until late 1917 to early 1918. Some units had as many as 26 or 27 reinforcement drafts. To provide officer reinforcements, a series of AIF officer schools, such as that at Broadmeadows, were established in Australia before officer training was eventually concentrated at a school near Duntroon. These schools produced a large number of officers, but they were eventually closed in 1917 due to concerns that their graduates were too inexperienced. After this most replacement officers were drawn from the ranks of the AIF's deployed units, and candidates attended either British officer training units, or in-theatre schools established in France. After February 1916, the issue of NCO training was also taken more seriously, and several schools were established, with training initially being two weeks in duration before being increased to two months.

After the AIF was transferred to the European battlefield, the training system was greatly improved. Efforts were made at standardisation, with a formal training organisation and curriculum—consisting of 14 weeks basic training for infantrymen—being established. In Egypt, as the AIF was expanded in early 1916, each brigade established a training battalion. These formations were later sent to the United Kingdom and were absorbed into a large system of depots that was established on Salisbury Plain by each branch of the AIF including infantry, engineers, artillery, signals, medical and logistics. After completing their initial instruction at depots in Australia and the United Kingdom, soldiers were posted to in-theatre base depots where they received advanced training before being posted as reinforcements to operational units. Like the British Army, the AIF sought to rapidly pass on "lessons learned" as the war progressed, and these were widely transmitted through regularly updated training documents. The experience gained through combat also improved the skills of the surviving officers and men, and by 1918 the AIF was a very well trained and well led force. After coming to terms with the conditions on the Western Front the Australians had played a part in the development of new combined arms tactics for offensive operations that occurred within the BEF, while in defence they employed patrolling, trench raids, and Peaceful Penetration tactics to dominate no man's land.

Following the deployment of the AIF a reinforcement system was used to replace wastage. Reinforcements received training in Australia first at camps around the country before sailing as drafts—consisting of about two officers and between 100 and 150 other ranks—and joining their assigned units at the front. Initially, these drafts were assigned to specific units prior to departure and were recruited from the same area as the unit they were assigned to, but later in the war drafts were sent as "general reinforcements", which could be assigned to any unit as required. These drafts were despatched even before Gallipoli and continued until late 1917 to early 1918. Some units had as many as 26 or 27 reinforcement drafts. To provide officer reinforcements, a series of AIF officer schools, such as that at Broadmeadows, were established in Australia before officer training was eventually concentrated at a school near Duntroon. These schools produced a large number of officers, but they were eventually closed in 1917 due to concerns that their graduates were too inexperienced. After this most replacement officers were drawn from the ranks of the AIF's deployed units, and candidates attended either British officer training units, or in-theatre schools established in France. After February 1916, the issue of NCO training was also taken more seriously, and several schools were established, with training initially being two weeks in duration before being increased to two months.

During the war the AIF gained a reputation, at least amongst British officers, for indifference to military authority and indiscipline when away from the battlefield on leave. This included a reputation for refusing to salute officers, sloppy dress, lack of respect for military rank and drunkenness on leave. Historian

During the war the AIF gained a reputation, at least amongst British officers, for indifference to military authority and indiscipline when away from the battlefield on leave. This included a reputation for refusing to salute officers, sloppy dress, lack of respect for military rank and drunkenness on leave. Historian

The first contingent of the AIF departed by ship in a single convoy from Fremantle, Western Australia and Albany on 1 November 1914. Although they were originally bound for England to undergo further training prior to employment on the Western Front, the Australians were subsequently sent to British-controlled Egypt to pre-empt any Turkish attack against the strategically important Suez Canal, and with a view to opening another front against the

The first contingent of the AIF departed by ship in a single convoy from Fremantle, Western Australia and Albany on 1 November 1914. Although they were originally bound for England to undergo further training prior to employment on the Western Front, the Australians were subsequently sent to British-controlled Egypt to pre-empt any Turkish attack against the strategically important Suez Canal, and with a view to opening another front against the

The advance entered Palestine and an

The advance entered Palestine and an

In March 1917, the 2nd and 5th Divisions pursued the Germans back to the

In March 1917, the 2nd and 5th Divisions pursued the Germans back to the

By the end of the war the AIF had gained a reputation as a well-trained and highly effective military force, enduring more than two years of costly fighting on the Western Front before playing a significant role in the final Allied victory in 1918, albeit as a smaller part of the wider British Empire war effort. Like the other Dominion divisions from Canada and New Zealand, the Australians were viewed as being among the best of the British forces in France, and were often used to spearhead operations. 64 Australians were awarded the

By the end of the war the AIF had gained a reputation as a well-trained and highly effective military force, enduring more than two years of costly fighting on the Western Front before playing a significant role in the final Allied victory in 1918, albeit as a smaller part of the wider British Empire war effort. Like the other Dominion divisions from Canada and New Zealand, the Australians were viewed as being among the best of the British forces in France, and were often used to spearhead operations. 64 Australians were awarded the

During and after the war, the AIF was often portrayed in glowing terms. As part of the "

During and after the war, the AIF was often portrayed in glowing terms. As part of the " Commemorating and celebrating the AIF became an entrenched tradition following World War I, with Anzac Day forming the centrepiece of remembrance of the war. The soldiers who served in the AIF, known colloquially as "

Commemorating and celebrating the AIF became an entrenched tradition following World War I, with Anzac Day forming the centrepiece of remembrance of the war. The soldiers who served in the AIF, known colloquially as "

First AIF Order of Battle 1914–1918

– Comprehensive database listing all servicemen of the 1st AIF

Discovering Anzacs

– locate an Australian serviceman, nurse or chaplain; add a note or photograph to complete their profile

Researching soldiers of World War 1

{{Authority control Australian Imperial Force 1 Military units and formations of the Australian Army Military units and formations of Australia in World War I Military units and formations established in 1914 Military units and formations disestablished in 1921 1914 establishments in Australia

Australian Army

The Australian Army is the principal land warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force. The Army is commanded by the Chief of Army (CA), wh ...

during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. It was formed as the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) following Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

's declaration of war on Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

on 15 August 1914, with an initial strength of one infantry division

Division or divider may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

*Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division

Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting ...

and one light horse brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute a division.

B ...

. The infantry division subsequently fought at Gallipoli between April and December 1915, with a newly raised second division, as well as three light horse brigades, reinforcing the committed units.

After being evacuated to Egypt, the AIF was expanded to five infantry divisions, which were committed to the fighting in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

and Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

along the Western Front in March 1916. A sixth infantry division was partially raised in 1917 in the United Kingdom, but was broken up and used as reinforcements following heavy casualties on the Western Front. Meanwhile, two mounted divisions remained in the Middle East to fight against Turkish forces in the Sinai and Palestine.The AIF included the Australian Flying Corps

The Australian Flying Corps (AFC) was the branch of the Australian Army responsible for operating aircraft during World War I, and the forerunner of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). The AFC was established in 1912, though it was not until ...

(AFC), the predecessor to the Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

, which consisted of four combat and four training squadrons that were deployed to the United Kingdom, the Western Front and the Middle East throughout the war.

An all volunteer

Volunteering is a voluntary act of an individual or group freely giving time and labor for community service. Many volunteers are specifically trained in the areas they work, such as medicine, education, or emergency rescue. Others serve ...

force, by the end of the war the AIF had gained a reputation as being a well-trained and highly effective military force, playing a significant role in the final Allied victory. However, this reputation came at a heavy cost with a casualty rate among the highest of any belligerent for the war. The remaining troops were repatriated until the disbandment of the 1st AIF between 1919 and 1921. After the war, the achievements of the AIF and its soldiers, known colloquially as "Diggers

The Diggers were a group of religious and political dissidents in England, associated with agrarian socialism. Gerrard Winstanley and William Everard, amongst many others, were known as True Levellers in 1649, in reference to their split from ...

", became central to the national mythology of the "Anzac legend

The Anzac spirit or Anzac legend is a concept which suggests that Australian and New Zealand soldiers possess shared characteristics, specifically the qualities those soldiers allegedly exemplified on the battlefields of World War I. These p ...

". Generally known at the time as ''the'' AIF, it is today referred to as the ''1st AIF'' to distinguish it from the Second Australian Imperial Force

The Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF, or Second AIF) was the name given to the volunteer expeditionary force of the Australian Army in the Second World War. It was formed following the declaration of war on Nazi Germany, with an initia ...

raised during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

.

Formation

At the start of the war, Australia's military forces were focused upon the part-timeMilitia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

. The small number of regular personnel were mostly artillerymen

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, ...

or engineers

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the ...

, and were generally assigned to the task of coastal defence. Due to the provisions of the ''Defence Act 1903'', which precluded sending conscripts overseas, upon the outbreak of war it was realised that a totally separate, all volunteer force would need to be raised. The Australian government pledged to supply 20,000 men organised as one infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

division

Division or divider may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

*Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division

Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting ...

and one light horse brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute a division.

B ...

plus supporting units, for service "wherever the British desired", in keeping with pre-war Imperial defence planning. The Australian Imperial Force (AIF) subsequently began forming shortly after the outbreak of war and was the brain child of Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

William Throsby Bridges

Major General Sir William Throsby Bridges, (18 February 1861 – 18 May 1915) was a senior Australian Army officer who was instrumental in establishing the Royal Military College, Duntroon and who served as the first Australian Chief of the ...

(later Major General) and his chief of staff, Major Brudenell White

General Sir Cyril Brudenell Bingham White, (23 September 1876 – 13 August 1940), more commonly known as Sir Brudenell White or C. B. B. White, was a senior officer in the Australian Army who served as Chief of the General Staff from 192 ...

. Officially coming into being on 15 August 1914, the word 'imperial' was chosen to reflect the duty of Australians to both nation and empire. The AIF was initially intended for service in Europe. Meanwhile, a separate 2,000-man force—known as the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF)—was formed for the task of capturing German New Guinea

German New Guinea (german: Deutsch-Neu-Guinea) consisted of the northeastern part of the island of New Guinea and several nearby island groups and was the first part of the German colonial empire. The mainland part of the territory, called , ...

. In addition, small military forces were maintained in Australia to defend the country from attack.

Upon formation, the AIF consisted of only one infantry division, the 1st Division, and the 1st Light Horse Brigade

The 1st Light Horse Brigade was a mounted infantry brigade of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), which served in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. The brigade was initially formed as a part-time militia formation in the early 1900s in ...

. The 1st Division was made up of the 1st Infantry Brigade under Colonel Henry MacLaurin, an Australian-born officer with previous part-time military service; the 2nd

A second is the base unit of time in the International System of Units (SI).

Second, Seconds or 2nd may also refer to:

Mathematics

* 2 (number), as an ordinal (also written as ''2nd'' or ''2d'')

* Second of arc, an angular measurement unit, ...

, under Colonel James Whiteside McCay

Lieutenant General Sir James Whiteside McCay, (21 December 1864 – 1 October 1930), who often spelt his surname M'Cay, was an Australian general and politician.

A graduate of the University of Melbourne, where he earned Master of Arts an ...

, an Irish-born Australian politician and former Minister for Defence

{{unsourced, date=February 2021

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is an often-used name for the part of a government responsible for matters of defence, found in states ...

; and the 3rd, under Colonel Ewen Sinclair-Maclagan, a British regular officer seconded to the Australian Army before the war. The 1st Light Horse Brigade was commanded by Colonel Harry Chauvel

General Sir Henry George Chauvel, (16 April 1865 – 4 March 1945) was a senior officer of the Australian Imperial Force who fought at Gallipoli and during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign in the Middle Eastern theatre of the First World W ...

, an Australian regular, while the divisional artillery was commanded by Colonel Talbot Hobbs

Lieutenant General Sir Joseph John Talbot Hobbs, (24 August 1864 – 21 April 1938) was an Australian architect and First World War general.

Early life

Hobbs was born in London, the son of Joseph and his wife Frances Ann Hobbs (née Wilson). E ...

. The initial response for recruits was so good that in September 1914 the decision was made to raise the 4th Infantry Brigade and 2nd

A second is the base unit of time in the International System of Units (SI).

Second, Seconds or 2nd may also refer to:

Mathematics

* 2 (number), as an ordinal (also written as ''2nd'' or ''2d'')

* Second of arc, an angular measurement unit, ...

and 3rd Light Horse Brigade

The 3rd Light Horse Brigade was a mounted infantry brigade of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), which served in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. The brigade was initially formed as a part-time militia formation in the early 1900s i ...

s. The 4th Infantry Brigade was commanded by Colonel John Monash

General (Australia), General Sir John Monash, (; 27 June 1865 – 8 October 1931) was an Australian civil engineer and military commander of the First World War. He commanded the 13th Brigade (Australia), 13th Infantry Brigade before the war an ...

, a prominent Melbourne civil engineer and businessman. The AIF continued to grow through the war, eventually numbering five infantry divisions, two mounted divisions and a mixture of other units. As the AIF operated within the British war effort, its units were generally organised along the same lines as comparable British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

formations. However, there were often small differences between the structures of British and Australian units, especially in regards to the AIF infantry divisions' support units.

Hastily deployed, the first contingent of the AIF was essentially untrained and suffered from widespread equipment shortages. In early 1915 the AIF was largely an inexperienced force, with only a small percentage of its members having previous combat experience. However, many officers and non-commissioned personnel (NCOs) had previously served in the pre-war permanent or part-time forces, and a significant proportion of the enlisted personnel had received some basic military instruction as part of Australia's compulsory training scheme. Predominantly a fighting force based on infantry battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions a ...

s and light horse regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscript ...

s—the high proportion of close combat troops to support personnel (e.g. medical, administrative, logistic, etc.) was exceeded only by the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF)—this fact at least partially accounted for the high percentage of casualties it later sustained. Nevertheless, the AIF eventually included a large number of logistics and administrative units which were capable of meeting most of the force's needs, and in some circumstances provided support to nearby allied units. However, the AIF mainly relied on the British Army for medium and heavy artillery support and other weapons systems necessary for combined arms

Combined arms is an approach to warfare that seeks to integrate different combat arms of a military to achieve mutually complementary effects (for example by using infantry and armour in an urban environment in which each supports the other) ...

warfare that were developed later in the war, including aircraft and tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engi ...

s.

Organisation

Command

When originally formed in 1914 the AIF was commanded by Bridges, who also commanded the 1st Division. After Bridges' death at Gallipoli in May 1915, the Australian government appointed

When originally formed in 1914 the AIF was commanded by Bridges, who also commanded the 1st Division. After Bridges' death at Gallipoli in May 1915, the Australian government appointed Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

James Gordon Legge

Lieutenant General James Gordon Legge, (15 August 1863 – 18 September 1947) was an Australian Army senior officer who served in the First World War and was the Chief of the General Staff, Australia's highest ranking army officer between 1914 ...

, a Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sou ...

veteran, to replace Bridges in command of both. However, British Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Sir John Maxwell, the commander of British Troops in Egypt

British Troops in Egypt was a command of the British Army.

History

A British Army commander was appointed in the late 19th century after the Anglo-Egyptian War in 1882. The British Army remained in Egypt throughout the First World War and, after t ...

, objected to Legge bypassing him and communicating directly with Australia. The Australian government failed to support Legge, who thereafter deferred to Lieutenant General William Birdwood

Field Marshal William Riddell Birdwood, 1st Baron Birdwood, (13 September 1865 – 17 May 1951) was a British Army officer. He saw active service in the Second Boer War on the staff of Lord Kitchener. He saw action again in the First World War ...

, the commander of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) was a First World War army corps of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. It was formed in Egypt in December 1914, and operated during the Gallipoli campaign. General William Birdwood com ...

. When Legge was sent to Egypt to command the 2nd Division, Birdwood made representations to the Australian government that Legge could not act as commander of the AIF, and that the Australian government should transfer Bridges' authority to him. This was done on a temporary basis on 18 September 1915. Promoted to major general, Chauvel took over command of the 1st Division in November when Major General Harold Walker was wounded, becoming the first Australian-born officer to command a division. When Birdwood became commander of the Dardanelles Army

The Dardanelles Army was formed in late 1915 and comprised the three army corps of the British Army operating at Gallipoli. It was created as a result of the reorganisation of headquarters when the second Mediterranean front opened at Salonika. ...

, command of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps and the AIF passed to another British officer, Lieutenant General Alexander Godley

General Sir Alexander John Godley, (4 February 1867 – 6 March 1957) was a senior British Army officer. He is best known for his role as commander of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force and II Anzac Corps during the First World War.

Born in ...

, the commander of the NZEF, but Birdwood resumed command of the AIF when he assumed command of II ANZAC Corps

The II ANZAC Corps (Second Anzac Corps) was an Australian and New Zealand First World War army corps. Formed in early 1916 in Egypt in the wake of the failed Gallipoli campaign, it initially consisted of two Australian divisions, and was sent t ...

upon its formation in Egypt in early 1916. I ANZAC Corps

The I ANZAC Corps (First Anzac Corps) was a combined Australian and New Zealand army corps that served during World War I.

It was formed in Egypt in February 1916 as part of the reorganisation and expansion of the Australian Imperial Force and ...

and II ANZAC Corps swapped designations on 28 March 1916. During early 1916 the Australian and, to a lesser extent, New Zealand governments sought the establishment of an Australian and New Zealand Army led by Birdwood which would have included all of the AIF's infantry divisions and the New Zealand Division

The New Zealand Division was an infantry division of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force raised for service in the First World War. It was formed in Egypt in early 1916 when the New Zealand and Australian Division was renamed after the detachmen ...

. However, General Douglas Haig

Field Marshal Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig, (; 19 June 1861 – 29 January 1928) was a senior officer of the British Army. During the First World War, he commanded the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front from late 1915 until ...

, the commander of the British Empire forces in France, rejected this proposal on the grounds that the size of these forces was too small to justify grouping them in a field army.

Birdwood was officially confirmed as commander of the AIF on 14 September 1916, backdated to 18 September 1915, while also commanding I ANZAC Corps on the Western Front. He retained overall responsibility for the AIF units in the Middle East, but in practice this fell to Godley, and after II ANZAC Corps left Egypt as well, to Chauvel who also commanded the ANZAC Mounted Division. Later promoted to lieutenant general, he subsequently commanded the Desert Mounted Corps

The Desert Mounted Corps was an army corps of the British Army during the First World War, of three mounted divisions renamed in August 1917 by General Edmund Allenby, from Desert Column. These divisions which served in the Sinai and Pales ...

of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force

The Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) was a British Empire military formation, formed on 10 March 1916 under the command of General Archibald Murray from the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force and the Force in Egypt (1914–15), at the beginning ...

; the first Australian to command a corps

Corps (; plural ''corps'' ; from French , from the Latin "body") is a term used for several different kinds of organization. A military innovation by Napoleon I, the formation was first named as such in 1805. The size of a corps varies great ...

. Birdwood was later given command of the Australian Corps

The Australian Corps was a World War I army corps that contained all five Australian infantry divisions serving on the Western Front. It was the largest corps fielded by the British Empire in France. At its peak the Australian Corps numbered 10 ...

on its formation in November 1917. Another Australian, Monash, by then a lieutenant general, took over command of the corps on 31 May 1918. Despite being promoted to command the British Fifth Army

The Fifth Army was a field army of the British Army during World War I that formed part of the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front between 1916 and 1918. The army originated as the Reserve Corps during the preparations for the Brit ...

, Birdwood retained command of the AIF. By this time four of the five divisional commanders were Australian officers. The exception was Major General Ewen Sinclair-Maclagan, the commander of the 4th Division, who was a British Army officer seconded to the Australian Army before the war, and who had joined the AIF in Australia in August 1914. The vast majority of brigade commands were also held by Australian officers. A number of British staff officers

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, enlisted and civilian staff who serve the commander of a division or other large military u ...

were attached to the headquarters of the Australian Corps, and its predecessors, due to a shortage of suitably trained Australian officers.

Structure

Infantry divisions

The organisation of the AIF closely followed the British Army divisional structure, and remained relatively unchanged throughout the war. During the war, the following infantry divisions were raised as part of the AIF: * 1st Division * 2nd Division * 3rd Division * 4th Division *5th Division In military terms, 5th Division may refer to:

Infantry divisions

* 5th Division (Australia)

*5th Division (People's Republic of China)

* 5th Division (Colombia)

*Finnish 5th Division (Continuation War)

* 5th Light Cavalry Division (France)

*5th Mo ...

* 6th Division (broken up in 1917 before seeing combat)

* New Zealand and Australian Division

The New Zealand and Australian Division was a composite army division raised for service in the First World War under the command of Major General Alexander Godley. Consisting of several mounted and standard infantry brigades from both New Zea ...

(1915)

Each division comprised three infantry brigades, and each brigade contained four battalions (later reduced to three in 1918). Australian battalions initially included eight rifle companies

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of people, whether natural, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specific, declared go ...

; however, this was reduced to four expanded companies in January 1915 to conform with the organisation of British infantry battalions. A battalion contained about 1,000 men. Although the divisional structure evolved over the course of the war, each formation also included a range of combat support and service units, including artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

, machine-gun

A machine gun is a automatic firearm, fully automatic, rifling, rifled action (firearms)#Autoloading operation, autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as Automatic shotgun, a ...

, mortar, engineer, pioneer

Pioneer commonly refers to a settler who migrates to previously uninhabited or sparsely inhabited land.

In the United States pioneer commonly refers to an American pioneer, a person in American history who migrated west to join in settling and de ...

, signals

In signal processing, a signal is a function that conveys information about a phenomenon. Any quantity that can vary over space or time can be used as a signal to share messages between observers. The ''IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing'' ...

, logistic, medical

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care practic ...

, veterinary

Veterinary medicine is the branch of medicine that deals with the prevention, management, diagnosis, and treatment of disease, disorder, and injury in animals. Along with this, it deals with animal rearing, husbandry, breeding, research on nutri ...

and administrative

Administration may refer to:

Management of organizations

* Management, the act of directing people towards accomplishing a goal

** Administrative Assistant, traditionally known as a Secretary, or also known as an administrative officer, administ ...

units. By 1918 each brigade also included a light trench mortar battery, while each division included a pioneer battalion, a machine-gun battalion, two field artillery brigades, a divisional trench mortar brigade, four companies of engineers, a divisional signals company, a divisional train

In rail transport, a train (from Old French , from Latin , "to pull, to draw") is a series of connected vehicles that run along a railway track and transport people or freight. Trains are typically pulled or pushed by locomotives (often ...

consisting of four service corps companies, a salvage company, three field ambulances, a sanitary section and a mobile veterinary section. These changes were reflective of wider organisational adaption, tactical innovation, and the adoption of new weapons and technology that occurred throughout the British Expeditionary Force (BEF).

At the start of the Gallipoli Campaign, the AIF had four infantry brigades with the first three making up the 1st Division. The 4th Brigade was joined with the sole New Zealand infantry brigade to form the New Zealand and Australian Division. The 2nd Division had been formed in Egypt in 1915 and was sent to Gallipoli in August to reinforce the 1st Division, doing so without its artillery and having only partially completed its training. After Gallipoli, the infantry underwent a major expansion. The 3rd Division was formed in Australia and completed its training in the UK before moving to France. The New Zealand and Australian Division was broken up with the New Zealand elements forming the New Zealand Division

The New Zealand Division was an infantry division of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force raised for service in the First World War. It was formed in Egypt in early 1916 when the New Zealand and Australian Division was renamed after the detachmen ...

, while the original Australian infantry brigades (1st to 4th) were split in half to create 16 new battalions to form another four brigades. These new brigades (12th to 15th) were used to form the 4th and 5th Divisions. This ensured the battalions of the two new divisions had a core of experienced soldiers. The 6th Division commenced forming in England in February 1917, but was never deployed to France and was broken up in September of that year to provide reinforcements to the other five divisions.

The Australian infantry did not have regiments in the British sense, only battalions identified by ordinal number (1st to 60th). Each battalion originated from a geographical region, with men recruited from that area. New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

and Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

, the most populous states, filled their own battalions (and even whole brigades) while the "Outer States"—Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

, South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

, Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

and Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

—often combined to assemble a battalion. These regional associations remained throughout the war and each battalion developed its own strong regimental identity. The pioneer battalions (1st to 5th, formed from March 1916) were also mostly recruited regionally; however, the machine-gun battalions (1st to 5th, formed from March 1918 from the brigade and divisional machine-gun companies) were made up of personnel from all states.

During the manpower crisis following the Third Battle of Ypres

The Third Battle of Ypres (german: link=no, Dritte Flandernschlacht; french: link=no, Troisième Bataille des Flandres; nl, Derde Slag om Ieper), also known as the Battle of Passchendaele (), was a campaign of the First World War, fought by t ...

, in which the five divisions sustained 38,000 casualties, there were plans to follow the British reorganisation and reduce all brigades from four battalions to three. In the British regimental system

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscripte ...

this was traumatic enough; however, the regimental identity survived the disbanding of a single battalion. In the Australian system, disbanding a battalion meant the extinction of the unit. In September 1918, the decision to disband seven battalions—the 19th

19 (nineteen) is the natural number following 18 and preceding 20. It is a prime number.

Mathematics

19 is the eighth prime number, and forms a sexy prime with 13, a twin prime with 17, and a cousin prime with 23. It is the third full re ...

, 21st, 25th

25 (twenty-five) is the natural number following 24 and preceding 26.

In mathematics

It is a square number, being 52 = 5 × 5. It is one of two two-digit numbers whose square and higher powers of the number also ends in the same last t ...

, 37th, 42nd

4 (four) is a number, numeral and digit. It is the natural number following 3 and preceding 5. It is the smallest semiprime and composite number, and is considered unlucky in many East Asian cultures.

In mathematics

Four is the smallest c ...

, 54th and 60th—led to a series of "mutinies over disbandment" where the ranks refused to report to their new battalions. In the AIF, mutiny was one of two charges that carried the death penalty, the other being desertion to the enemy. Instead of being charged with mutiny, the instigators were charged as being absent without leave

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or post without permission (a pass, liberty or leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with unauthorized absence (UA) or absence without leave (AWOL ), which a ...

(AWOL) and the doomed battalions were eventually permitted to remain together for the forthcoming battle, following which the survivors voluntarily disbanded. These mutinies were motivated mainly by the soldiers' loyalty to their battalions.

The artillery underwent a significant expansion during the war. When the 1st Division embarked in November 1914 it did so with its 18-pounder

The Ordnance QF 18-pounder,British military traditionally denoted smaller ordnance by the weight of its standard projectile, in this case approximately or simply 18-pounder gun, was the standard British Empire field gun of the First World War ...

field guns, but Australia had not been able to provide the division with the howitzer batteries or the heavy guns that would otherwise have been included on its establishment, due to a lack of equipment. These shortages were unable to be rectified prior to the landing at Gallipoli where the howitzers would have provided the plunging and high-angled fire that was required due to the rough terrain at Anzac Cove. When the 2nd Division was formed in July 1915 it did so without its complement of artillery. Meanwhile, in December 1915 when the government offered to form another division it did so on the basis that its artillery would be provided by Britain. In time though these shortfalls were overcome, with the Australian field artillery expanding from just three field brigades in 1914 to twenty at the end of 1917. The majority of the heavy artillery units supporting the Australian divisions were British, although two Australian heavy batteries were raised from the regular Australian Garrison Artillery. These were the 54th Siege Battery, which was equipped with 8-inch howitzers, and the 55th with 9.2-inch howitzers.

Mounted divisions

The following mounted divisions were raised as part of the AIF: * ANZAC Mounted Division *Australian Mounted Division

The Australian Mounted Division originally formed as the Imperial Mounted Division in January 1917, was a mounted infantry, light horse and yeomanry division. The division was formed in Egypt, and along with the Anzac Mounted Division formed p ...

During the Gallipoli Campaign four light horse brigades had been dismounted and fought alongside the infantry divisions. However, in March 1916 the ANZAC Mounted Division was formed in Egypt (so named because it contained one mounted brigade from New Zealand – the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade

The New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade was a brigade of the New Zealand Army during the First World War. Raised in 1914 as part of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, it was one of the first New Zealand units to sail for service overseas.

The ...

). Likewise, the Australian Mounted Division—formed in February 1917—was originally named the Imperial Mounted Division because it contained the British 5th

Fifth is the ordinal form of the number five.

Fifth or The Fifth may refer to:

* Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, as in the expression "pleading the Fifth"

* Fifth column, a political term

* Fifth disease, a contagious rash tha ...

and 6th Mounted Brigade

The 2nd South Midland Mounted Brigade (later numbered as the 6th Mounted Brigade) was a yeomanry brigade of the British Army, formed as part of the Territorial Force in 1908.

It served dismounted in the Gallipoli Campaign before being remounte ...

s. Each division consisted of three mounted light horse brigades. A light horse brigade consisted of three regiments. Each regiment included three squadrons of four troops

A troop is a military sub-subunit, originally a small formation of cavalry, subordinate to a squadron. In many armies a troop is the equivalent element to the infantry section or platoon. Exceptions are the US Cavalry and the King's Troo ...

and a machine-gun section. The initial strength of a regiment was around 500 men, although its establishment changed throughout the war. In 1916, the machine-gun sections of each regiment were concentrated as squadrons at brigade-level. Like the infantry, the light horse regiments were raised on a territorial basis by state and were identified numerically (1st to 15th).

Corps

The following corps-level formations were raised: * Australian and New Zealand Army Corps * I ANZAC Corps * II ANZAC Corps * Australian Corps * Desert Mounted Corps (formerly theDesert Column

The Desert Column was a First World War British Empire army corps which operated in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign from 22 December 1916.There is no war diary for Desert Column for December. See The Column was commanded by Lieutenant General ...

)

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) was formed from the AIF and NZEF in preparation for the Gallipoli Campaign in 1915 and was commanded by Birdwood. Initially the corps consisted of the 1st Australian Division, the New Zealand and Australian Division, and two mounted brigades—the Australian 1st Light Horse Brigade and the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade—although when first deployed to Gallipoli in April, it did so without its mounted formations, as the terrain was considered unsuitable. However, in May, both brigades were dismounted and deployed along with the 2nd and 3rd Light Horse Brigades as reinforcements. Later, as the campaign continued the corps was reinforced further by the 2nd Australian Division, which began arriving from August 1915. In February 1916, it was reorganised into I and II ANZAC Corps in Egypt following the evacuation from Gallipoli and the subsequent expansion of the AIF.

I ANZAC Corps included the Australian 1st and 2nd Divisions and the New Zealand Division. The New Zealand Division was later transferred to the II ANZAC Corps in July 1916 and was replaced by the Australian 3rd Division in I ANZAC. Initially employed in Egypt as part of the defence of the Suez Canal, it was transferred to the Western Front in March 1916. II ANZAC Corps included the Australian 4th and 5th Divisions, forming in Egypt it transferred to France in July 1916. In November 1917 the five Australian divisions of I and II ANZAC Corps merged to become the Australian Corps, while the British and New Zealand elements in each corps became the British XXII Corps. The Australian Corps was the largest corps fielded by the British Empire in France, providing just over 10 percent of the manning of the BEF. At its peak it numbered 109,881 men. Corps troops raised included the 13th Light Horse Regiment and three army artillery brigades. Each corps also included a cyclist battalion.

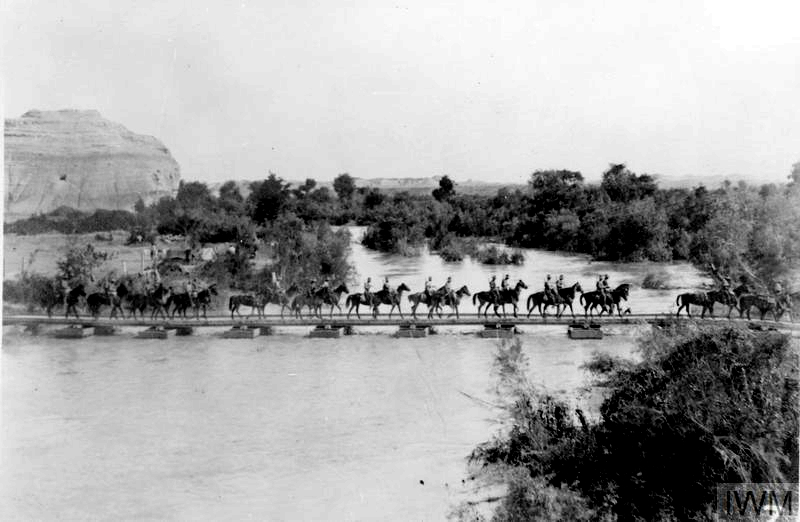

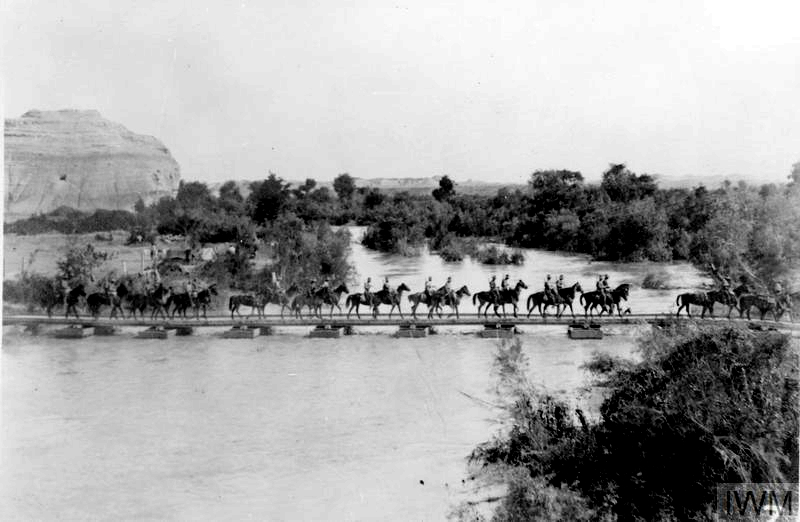

Meanwhile, the majority of the Australian Light Horse had remained in the Middle East and subsequently served in Egypt, Sinai, Palestine and Syria with the Desert Column of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force. In August 1917 the column was expanded to become the Desert Mounted Corps, which consisted of the ANZAC Mounted Division, Australian Mounted Division and the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade

The Imperial Camel Corps Brigade (ICCB) was a camel-mounted infantry brigade that the British Empire raised in December 1916 during the First World War for service in the Middle East.

From a small beginning the unit eventually grew to a bri ...

(which included a number of Australian, British and New Zealand camel companies). In contrast to the static trench warfare

Trench warfare is a type of land warfare using occupied lines largely comprising military trenches, in which troops are well-protected from the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from artillery. Trench warfare became ar ...

that developed in Europe, the troops in the Middle East mostly experienced a more fluid form of warfare involving manoeuvre and combined arms tactics.

Australian Flying Corps

The 1st AIF included the

The 1st AIF included the Australian Flying Corps

The Australian Flying Corps (AFC) was the branch of the Australian Army responsible for operating aircraft during World War I, and the forerunner of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). The AFC was established in 1912, though it was not until ...

(AFC). Soon after the outbreak of war in 1914, two aircraft were sent to assist in capturing German colonies in what is now north-east New Guinea. However, these colonies surrendered quickly, before the planes were even unpacked. The first operational flights did not occur until 27 May 1915, when the Mesopotamian Half Flight

The Mesopotamian Half-Flight (MHF), or Australian Half-Flight, was the first Australian Flying Corps (AFC) unit to see active service during World War I. Formed in April 1915 at the request of the Indian Government, the half-flight's personnel w ...

was called upon to assist the Indian Army

The Indian Army is the land-based branch and the largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head is the Chief of Army Staff (COAS), who is a four- ...

in protecting British oil interests in what is now Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and K ...

. The corps later saw action in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

, Palestine and on the Western Front throughout the remainder of World War I. By the end of the war, four squadrons— Nos. 1, 2, 3 and 4—had seen operational service, while another four training squadrons— Nos. 5, 6, 7 and 8—had also been established. A total of 460 officers and 2,234 other ranks served in the AFC. The AFC remained part of the Australian Army until 1919, when it was disbanded; later forming the basis of the Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

.

Specialist units

A number of specialist units were also raised, including three Australian tunnelling companies. Arriving on the Western Front in May 1916 they undertook mining and counter-mining operations alongside British, Canadian and New Zealand companies, initially operating around Armentieres and atFromelles

Fromelles () is a commune in the Nord department in northern France. it had a population of 1,041; its inhabitants are called ''Fromellois''. It is located about to the west of Lille.

First World War

The village of Fromelles was captured by a ...

. The following year they operated in the Ypres

Ypres ( , ; nl, Ieper ; vls, Yper; german: Ypern ) is a Belgian city and municipality in the province of West Flanders. Though

the Dutch name is the official one, the city's French name is most commonly used in English. The municipality c ...

section. In November 1916, the 1st Australian Tunnelling Company

The 1st Australian Tunnelling Company was one of the tunnelling companies of the Royal Australian Engineers during World War I. The tunnelling units were occupied in offensive and defensive mining involving the placing and maintaining of mines ...

took over from the Canadians around Hill 60, subsequently playing a key role in the Battle of Messines in June 1917. During the German offensive in March 1918 the three companies served as infantry, and later supported the Allied advance being used to defuse booby traps and mines. The Australian Electrical Mining and Mechanical Boring Company supplied electric power to units in the British Second Army

The British Second Army was a field army active during the First and Second World Wars. During the First World War the army was active on the Western Front throughout most of the war and later active in Italy. During the Second World War the army ...

area.

Motor transport units were also formed. Not required at Gallipoli, they were sent on to the Western Front, becoming the first units of the AIF to serve there. The motor transport rejoined I ANZAC Corps when it reached the Western Front in 1916. Australia also formed six railway operating companies, which served on the Western Front. Specialist ordnance units included ammunition and mobile workshops units formed late in the war, while service units included supply columns, ammunition sub-parks, field bakeries and butcheries, and depot units. Hospitals and other specialist medical and dental units were also formed in Australia and overseas, as were a number of convalescent depots.

One small armoured unit was raised, the 1st Armoured Car Section. Formed in Australia, it fought in the Western Desert, and then, re-equipped with T Model Fords, served in Palestine as the 1st Light Car Patrol. Camel companies were raised in Egypt to patrol the Western Desert. They formed part of the Imperial Camel Corps

The Imperial Camel Corps Brigade (ICCB) was a camel-mounted infantry brigade that the British Empire raised in December 1916 during the First World War for service in the Middle East.

From a small beginning the unit eventually grew to a brigad ...

and fought in the Sinai and Palestine. In 1918 they were converted to light horse as the 14th and 15th Light Horse Regiments.

Administration

Although operationally placed at the disposal of the British, the AIF was administered as a separate national force, with the Australian government reserving the responsibility for the promotion, pay, clothing, equipment and feeding of its personnel. The AIF was administered separately from the home-based army in Australia, and a parallel system was set up to deal with non-operational matters including record-keeping, finance, ordnance, personnel, quartermaster and other issues. The AIF also had separate conditions of service, rules regarding promotion and seniority, and graduation list for officers. This responsibility initially fell to Bridges, in addition to his duties as its commander; however, an Administrative Headquarters was later set up inCairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the Capital city, capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, List of ...

in Egypt. Following the redeployment of the Australian infantry divisions to the Western Front it was relocated to London. Additional responsibilities included liaison with the British War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the new Ministry of Defence (MoD). This article contains text from ...

as well as the Australian Department of Defence Department of Defence or Department of Defense may refer to:

Current departments of defence

* Department of Defence (Australia)

* Department of National Defence (Canada)

* Department of Defence (Ireland)

* Department of National Defense (Philipp ...

in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

, whilst also being tasked with the command of all Australian troops in Britain. A training headquarters was also established at Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of ...

. The AIF Headquarters and its subordinate units were almost entirely independent from the British Army, which allowed the force to be self-sustaining in many fields. The AIF generally followed British administrative policy and procedures, including for the awarding of imperial honours and awards.

Weaponry and equipment

The weaponry and equipment of the Australian Army had mostly been standardised on that used by the British Army prior to the outbreak of World War I. During the war the equipment used changed as tactics evolved, and generally followed British developments. The standard issued rifle was the .303-inch Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mark III (SMLE). Infantrymen used 1908-pattern webbing, while light horsemen used leather

The weaponry and equipment of the Australian Army had mostly been standardised on that used by the British Army prior to the outbreak of World War I. During the war the equipment used changed as tactics evolved, and generally followed British developments. The standard issued rifle was the .303-inch Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mark III (SMLE). Infantrymen used 1908-pattern webbing, while light horsemen used leather bandolier

A bandolier or a bandoleer is a pocketed belt for holding either individual bullets, or belts of ammunition. It is usually slung sash-style over the shoulder and chest, with the ammunition pockets across the midriff and chest. Though functiona ...

s and load carriage equipment. A large pack was issued as part of marching order. In 1915 infantrymen were issued with the SMLE and long sword bayonet, while periscope rifles were also used. From 1916 they also used manufactured hand grenades and rodded rifle grenade

A rifle grenade is a grenade that uses a rifle-based launcher to permit a longer effective range than would be possible if the grenade were thrown by hand.

The practice of projecting grenades with rifle-mounted launchers was first widely used dur ...

s, both of which had been in short supply at Gallipoli (necessitating the use of improvised "jam-tin" grenades). A grenade discharge cup was issued for fitting to the muzzle of a rifle for the projection of the Mills bomb

"Mills bomb" is the popular name for a series of British hand grenades which were designed by William Mills. They were the first modern fragmentation grenades used by the British Army and saw widespread use in the First and Second World Wa ...

from 1917. Machine-guns initially included a small number of Maxim

Maxim or Maksim may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Maxim'' (magazine), an international men's magazine

** ''Maxim'' (Australia), the Australian edition

** ''Maxim'' (India), the Indian edition

*Maxim Radio, ''Maxim'' magazine's radio channel on Sir ...

or Vickers medium machine-guns, but subsequently also included the Lewis light machine-gun, the latter two of which were issued in greater numbers as the war continued so as to increase the firepower available to the infantry in response to the tactical problems of trench warfare. Light horse units underwent a similar process, although were issued Hotchkiss guns to replace their Lewis guns in early 1917.

From 1916 the Stokes light trench mortar was issued to infantry to replace a range of trench catapults and smaller trench mortars, whilst it was also used in a battery at brigade-level to provide organic indirect fire support. In addition, individual soldiers often used a range of personal weapons including knives, clubs, knuckle-dusters, revolvers and pistols. Snipers on the Western Front used Pattern 1914 Enfield

The Rifle, .303 Pattern 1914 (or P14) was a British service rifle of the First World War period. A bolt action weapon with an integral 5-round magazine, it was principally contract manufactured by companies in the United States. It served as ...

sniper rifles with telescopic sights. Light horsemen also carried bayonets (as they were initially considered mounted infantry

Mounted infantry were infantry who rode horses instead of marching. The original dragoons were essentially mounted infantry. According to the 1911 ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', "Mounted rifles are half cavalry, mounted infantry merely specially m ...

), although the Australian Mounted Division adopted cavalry swords in late 1917. Artillery included 18-pounders which equipped the field batteries, 4.5-inch howitzers used by the howitzer batteries, and 8-inch and 9.2-inch howitzers which equipped the heavy (siege) batteries. The 9.45-inch heavy mortar equipped a heavy trench mortar battery, while medium trench mortar batteries were equipped with the 2-inch medium mortar

The 2 inch medium trench mortar, also known as the 2-inch howitzer, and nicknamed the " toffee apple" or "plum pudding" mortar, was a British smooth bore muzzle loading (SBML) medium trench mortar in use in World War I from mid-1915 to mid-19 ...

, and later the 6-inch mortar. Light Horse units were supported by British and Indian artillery. The main mount used by the light horse was the Waler

The Waler is an Australian breed of horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has ...

, while draught horses were used by the artillery and for wheeled transport. Camels were also used, both as mounts and transport, and donkeys and mules were used as pack animals.

Personnel

Recruitment

Enlisted under the ''Defence Act 1903'', the AIF was an allvolunteer

Volunteering is a voluntary act of an individual or group freely giving time and labor for community service. Many volunteers are specifically trained in the areas they work, such as medicine, education, or emergency rescue. Others serve ...

force for the duration of the war. Australia was one of only two belligerents on either side not to introduce conscription during the war (along with South Africa). Although a system of compulsory training had been introduced in 1911 for home service, under Australian law it did not extend to overseas service. In Australia, two plebiscites on using conscription to expand the AIF were defeated in October 1916 and December 1917, thereby preserving the volunteer status but stretching the AIF's reserves towards the end of the war. A total of 416,809 men enlisted in the Army during the war, representing 38.7 percent of the white male population aged between 18 and 44. Of these, 331,781 men were sent overseas to serve as part of the AIF. Approximately 18 percent of those who served in the AIF had been born in the United Kingdom, marginally more than their proportion of the Australian population, although almost all enlistments occurred in Australia, with only 57 people being recruited from overseas. Indigenous Australians were officially barred from the AIF until October 1917, when the restrictions were altered to allow so-called "half-castes" to join. Estimates of the number of Indigenous Australians who served in the AIF differ considerably, but are believed to be over 500. More than 2,000 women served with the AIF, mainly in the Australian Army Nursing Service

The Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) was an Australian Army Reserve unit which provided a pool of trained civilian nurses who had volunteered for military service during wartime. The AANS was formed in 1902 by amalgamating the nursing servic ...

.

The recruitment process was managed by the various military districts. At the outset it had been planned to recruit half the AIF's initial commitment of 20,000 personnel from Australia's part-time forces, and volunteers were initially recruited from within designated regimental areas, thus creating a linkage between the units of the AIF and the units of the home service Militia. In the early stages of mobilisation the men of the AIF were selected under some of the toughest criterion of any army in World War I and it is believed that roughly 30 percent of men that applied were rejected on medical grounds. To enlist, men had to be aged between 18 and 35 years of age (although it is believed that men as old as 70 and as young as 14 managed to enlist), and they had to be at least , with a chest measurement of at least . Many of these strict requirements were lifted later in the war, however, as the need for replacements grew. Indeed, casualties among the initial volunteers were so high, that of the 32,000 original soldiers of the AIF only 7,000 would survive to the end of the war.